(This was originally published on polytheist.com December 2014. This article was my first introduction to what will formulate as The Dionysian Artist and vitally important to me as a progression piece. As such it is not as refined as I’d like, but merits recording.)

This article is dedicated to the leaders of the troop, the singers and dancers, actors and pantomimes, writers and musicians, acrobats and magicians, painters, illustrators and sculptors – The Dionysian Artists.

Mille viae ducunt homines per saecula Romam – A thousand roads lead men forever to Rome.

I ponder on this phrase a lot, typically it means: all paths lead to the same destination, but my feelings of it go back further. I like to believe that all roads lead to the founding of civilisation – in a literal sense – in that the streets and roads are the birthplace of our culture particularly through street performance.

In 2008 two hermit artists decided to do something pretty dramatic, well, at least for them. They decided to go out into the streets of a major metropolitan city and draw on the pavement for donations. My partner and I soon discovered the power of the street.

The knowledge and physical wealth that it grants. My perspective of the street changed overnight, no longer did I consider those busking or working on the street to be lowly, instead I quickly develop an admiration and love for the street. Street culture is a fascinating subject, in some ways it’s part of the overall culture but also separate of it. There are unspoken laws, unique slang, obscure subcultures and most importantly unrecognised traditions that can be traced to ancient times. Street performers are often outsiders who don’t follow the social norms that has been expected of them, many are freaks and weirdos, most are extremely talented and either completely mad or incredibly wise, or a bit of both.

In some respects I view busking or street performance as an actual magical rite, performers perform a ritual, they finish and hold out a hat and get money from nowhere. Away from earnings, they transform the commonplace environment of the street into a domain of miracles with feats of disbelief. I have never witnessed such direct and consistent magic like street performance. I don’t think it’s mere coincidence that terms used in reference to magic are similar or identical terms used in art: craft, spell, act, art. It is also interesting that Street Magic is still performed today and in fact many street magicians use tricks, symbols and colours that were used in ancient times.

Through my profession and my own spiritual practice I started witnessing uncanny connections between performance and my beliefs, exploring this subject has resulted in this article.

Ancient Greek religion was unique at the time because unlike some other cultures it was based around household worship, community and polis. In some cases priests were elected from the general population, religious titles and positions were granted to common people. Interacting and communing with the divine was not exclusive to just the elite or ordained priest, everyone was entitled to participate and later there were rites in which even slaves were allowed.

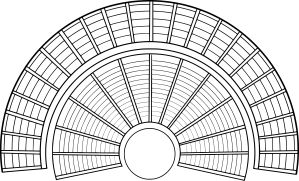

One of the most important and unique developments of this faith was the theatre. I suspect the theatre had humble origins beginning with bards that would travel from town to town reciting epic Homeric stories on the side of the road or in the local agora. As their reputation developed more people would gather on grassy hills to see these bards perform. Slowly these bards incorporated other performers who mimed, danced, played music etc. Over time actors were given lines and the hills were carved out into an amphitheatre. What started as a simple impromptu act by travelling performers turned into an organised community service.

The theatre was not just for entertainment, it held multiple functions as a gathering place. Plays themselves were considered sacred performances, Tragedy is usually consider the foremost important form. The origins of Tragedy was lost in ancient Greece, where scholars like Aristotle and Athenaeus of Naucratis debated the etymology of the word. In general, Tragedy is commonly believed to originate from τραγῳδία trag(o)-aoidiā “goat song” meaning that it may of involved some form of ritual sacrifice. It is agreed that it is related to the god Dionysos. Richard Seaford suggests Tragedy evolved from some form of Satyr play related to the Dionysian mysteries which possibly enacted the death, rebirth of Dionysos – these performances were intense and involved audience participation, the mystery rites later became free for public viewing:

At the Dionysiac festivals the citizens en masse watched the ritual impersonation of myth on the streets, but were excluded from the mystic ritual at the heart of the festival. And so not only was the traditional processional hymn transformed into a scripted stationary hymn under a hillside (so that all could see), but also the irresistibly secret sights of mystic ritual were opened out to the curious gaze of the entire polis. Greek ritual tends to enact its own aetiological myth, and the first tragedies were, I suspect, dramatisations of the aetiological myths enacted in mystery-cult – as was, a century later, the highly traditional Bacchae.” (1)

In some respects the theatre was place of religious observance similar to how one might view a church. The performers were taking on the role of religious spokesmen. By the time fifth century BC Athenian Golden Age of drama playwrights were writing plays with the same themes as the mystery performance but incorporating other tales. So the essence of being confronted with death was still present but transformed into another new narrative to maintain audience enthusiasm.

Also to maintain audience enthusiasm and to prevent them leaving the theatre depressed was the comedies which were performed as intermission plays between the tragedies. These light hearted plays sometimes involved actors dressed as satyrs (with a long red leather phallus around their waist) the plays would parody classical stories. For example the only surviving satyr play, Cyclops by Euripides features Odysseus saving Silenus and his troop of satyrs from the cruelty and sexual molestation of the Cyclops, Polyphemus. Other times they involved a serious debate or dire situation that results in some silly happy ending.

The origins of Comedy appear to be ancient even in classical times. The term comedy is usually considered derived from Kom-oid meaning “party song” and may have had its origins as some silly drunken mockery. Obviously related directly with Dionysian festivals. Compared with tragedy its origins are confusing. It appears that it was imported into Athens via the Dorians in what is called the Dorian farce. Athenian comedy originally seems to be focused on nonsense and impromptu with only a loose story. Dramatic comedy being introduced from Sicily and evolved into a proper narrative as mentioned by Aristotle in Poetics 5.1449b:

The making of tales (i.e. plots) originally came from Sicily, but of the Athenians Crates first began, by discarding the abusive scheme as a whole, to construct stories and tales.” (2)

This is further evident as Athenian Old Comedy writer, Aristophanes references the Dorian Colonies of Magna Graecia in Wasps, for their farces which he considered low-class for its obscene humour, slap stick and sexual themes.

Don’t expect anything profound,

Or any slapstick à la Megara.

And we got no slaves to dish out baskets

Of free nuts—or the old ham scene

Of Heracles cheated of his dinner;

… Our little story

Had meat in it and a meaning not

Too far above your heads, but more

Worth your attention than low comedy.

(3)

Still Aristophanes employed the themes in his comedies. His criticisms appear to be attempts to prop up his own plays over Magna Graecia, where it looks like native writers were the inventors of the first comedic plot.

Old comedy also featured something pretty radical, it was used as a platform to ridicule and lampoon people of importance, such as leaders, nobility and even gender statuses. I consider this the birth of free speech, especially after the theatre became a domain of politics with politicians holding debates or speeches before plays. Regardless, as the art form developed (and possible political problems) comedy became more focused on archetypical stock characters. These characters deviated from anyone in particular and are notable for a lack of mythic or religious figures, instead they are stock characters based on everyday life: courtesans, revellers, parasites, angry cooks and soldiers etc. This is considered Middle Comedy. From here comedy disappeared from history in Greece as none of the play survived, until it had a resurgence during the reign of Alexander as New Comedy.

However the Italians had a different sense of humour to the Athenians and maintained and expanded the traditions of comedy. An especially fascinating aspect is found in Tarentum (Taranto) where comedy was incorporated into female initiation rites and was performed for girls entering maidenhood:

Rhinthon, who was born in Syracuse but worked in Taras/Tarentum, has earned the reputation of expanding the genre of tragi-comedy, subverting some of the Attic conventions. It is very likely that his plays were performed in the theater at Locri, and the presence of a phlyax figure in the Grotta suggests that Locrian women enjoyed the sophistication and wit he represents.

[…] There may have been actual theatrical performances in the cave: among the votive objects were miniature models of the Grotta on which curtains were carved in relief. Terracotta figurines of comic actors and musicians, along with masks, indicate the importance of the theater to the votaries. The chiaroscuro mix of the serious and the comic, like the interplay between death and life, would be appropriate for the rituals in a nymphaeum.” (4)

(Again returning back to what Seaford mentions about satyr plays and mystery rites.)

The comedy in Italy of utmost importance in this essay as it is the link between classical comedy and the Middle-Age Commedia dell’Arte. The stock characters found in Middle comedy in Greece are direct precursors to the future Harlequin and Pierrot (which will be discussed later).

Before and after Alexander, performing troops became highly respected in Greece. It appears that they were formalised into an official professional guild called, Dionysiakoi Technitai (Artists of Dionysos) where they were granted unprecedented privileges. The Debate, On the False Embassy, 348 BC, specifically states that the first two ambassadors from Athens to negotiate peace with Philip II were tragic actors and poets:

Aristodemos and Neoptolemos were Tragic actors. Because of their profession these men had safe-conduct to go wherever they wished, even into enemy territory.” (5)

Phillip’s high regard for these actors was seen as corruption by critics in Athens, even going as far as claiming the actors were serving their own interests over the city’s. Of a particular note Neoptolemos sung a tragic ode to Phillip the night before his daughter’s wedding, which was later seen as an ill omen. It was during the wedding that Phillip was assassinated in the theatre. (While no links are found in history, I love fantasying of a conspiracy by the actors.)

By 279 BC a Delphic decree by the Athenian state was written in marble granting these artists immunity within all Greece: any harm, taxation or conscription was forbidden against them. (6) These marbles were followed up with a number of congratulatory awards naming performers and those that worked for the Technitai including carpenters, prop makers and background artists. In The Context of Ancient Drama by Eric Csapo & William Slater they claim that this organisation was the first trade union. However I feel that because the guild appears to have its own internal autonomous government structure, which was completely apart from any other state government, it was more akin to the Papal State. This is evident in the Delphic decrees as they emphasis religious services performed by the Technitai moreover than their acting abilities. To return back to the Mysteries cults of Greece, there are strong ties within these rites and performance. The Technitai would had been the ones that performed the sacred plays and also the ones that knew all the mysteries. They were not mere actors, but diplomats, spies and the highest priests of the time. Their power became so prominent they were allowed to wear distinctive clothing and regal items to prove their association to the guild and also their authority, including purple robes, crowns and golden jewels bearing their insignia.

Perhaps it is completely unrelated, but in less than one hundred years after the Delphic decree Rome outlawed and committed a massive purge of the Dionysian cult in 186 BC with declaration of the senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus. Livy wrote a fantastical account for the reason why in History of Rome (7), claiming that members of the cult were performing evil nocturnal rites that involved either extorting or killing nobility to gain their inheritance with an intended conspiracy against the Republic. I wonder if the Technitai (who were the Dionysian cult) was the real threat behind this drastic action? Whatever the case, the Technitai continued to exist throughout Roman imperialism even into Christian times. What humbly begun on the streets in time became a powerful international organisation.

Apart from the organisation of the Dionysiakoi Technitai there were also independent street performers throughout Greece and Rome. With exception of the laws mentioned from the Twelve Tables and some minor laws preventing ranked Roman officers and members of the senate from viewing or participating, these performers appeared to be free to perform wherever.

They may of even been supported by the state to please the mob during festivals. A distinctive trait of these travelling performers was the Phylakes stage, a portable stage made of boards that allowed actors, poets and dancers to perform. This mobility allowed them to follow the rustic Dionysian processions that would spread out from the cities after religious festivals. While their performances may of copied classical plays these street actors are most often mentioned for their crass and lewd comedic performances.

Of interest, these independent performers also did other forms of street performance such as street magic, Alciphron of Athens (unknown date, possibly between 170 and 350 CE) is one of the few that records the classic cups and balls routine. He mentions being “rendered speechless and gaped with surprise” as he watched a street performer:

A man came forward and placed on a three-legged table three small dishes, under which he concealed some little white round pebbles. These he placed one by one under the dishes, and then, I do not know how, he made them all appear all together under one.

At other times he made them disappear from beneath the dishes and showed them in his mouth. Next, when he had swallowed them, he brought those who stood nearest him into the middle, and then pulled one stone from the nose, another from the ear, and another from the head of the man standing near him.

Finally he caused the stones to vanish from the sight of everyone. He is a most dexterous fellow and even beyond Eurybates of Oechalia, of whom we heard so much.” (8)

(Note: Eurybates of Oechalia is a famous thief mentioned in previous letters)

There are few classical sources of these performers with only vague references in law and mention of preference for performers to set up on crossroads or outside places of worship. Crossroads were a place of mystery for Ancient people and associated with the gods Hermes and Hekate. Two divinities of magic, chthonic gods as guide and guard of the dead. (Hermes is also inclusive of travel, begging, rustic performance, con-men, thieves, trade and money.)

Here is where I start to wonder if these people were not just performers for entertainment purposes but played a role as a poor man’s celebrant and priest? Was street magic enough proof by performers to act as a charlatan and quack doctor?

Plato is quite critical of what he describes as so called Orphic priests:

Begging priests and prophets frequent the doors of the rich and persuade them that they possess a god–given power founded on sacrifices and incantations.” (9)

The Orphic cult itself is based around the legendary traveling musician and prophet of Dionysos, Orpheus, who ventured into hades to free his beloved from death. While in the realm he witnessed the mysteries of death and after failing in his original task went about teaching the mysteries in what would become Orphism. The traditions, myths and rituals differ from time, place and possibly priest, but there is a shared concept that those initiated into its mysteries are free from continual reincarnation of mortality and are able to enjoy an eternity feasting with gods and other initiated.

An interesting aspect of this cult are the gold leaf tablets or scrolls left with the dead that instruct the soul of the correct destination to be free of reincarnation. These tablets have been found all over the Hellenistic world from Thrace, to Sicily and Crete, all share similar characteristics, however some are poorly made while others are elaborate. The most amateur tablets feature spelling mistakes, incorrect instructions, some are simply blank. Is this proof of hacks jumping on the band wagon to fool a grieving family after the loss of a loved one? Were these hacks travelling performers who proved their power with parlour tricks? I can only guess.

An aspect of ancient funeral rites, especially in Italy was that funerals were not solemn, at least not how they are in the west now. Livy actually marks the year 328 BC for two significant events, the founding of the colony at Fregellae and the meat served at the funeral of the mother of M. Flavius. (10) Funerals were used by Romans to demonstrate the wealth and power of the family after the death, they would involve massive public feasts, games and performance.

Apart from politics funerals were a celebration of life and performers found themselves in the role of celebrates where they lead a triumphant procession of the body to the tomb – the tomb itself was often elaborately decorated with Dionysian scenes. Festivals, performances and tombs are reassurances for the living, to prove that life after death is a good thing. Plays aided in that distraction. When viewing or participating both audience and actors have to remove themselves from their current situation and identity. One must suspend their thoughts to comprehend the “fantasy” in front of them, performance in itself is a form of release. What better way to recover from grief then be submerged within a fantasy. To return back to the independent street performers, did they involve themselves in these funeral performances or offer their services to rural folk too?

An interesting point by Dionysian polytheist author, H. Jeremiah Lewis (11) is the colour schemes shared with street performance throughout history and also magical ritual in classical times, particularly in regards to Orphism. White, red and black are colours that make up a dusky dark cloak worn by Medea in the Orphic Argonautika in Greek it is called: ὄρφνῐνος orphninos. The colours are also mentioned in a Bulgarian healing ritual where each are related to the varying realms of heaven, earth and the underworld. Much later times the colours are worn by harlequins, clowns and street magicians in what was originally street shows, the Middle-Age Commedia dell’Arte. I suspect that the colour scheme goes as far as the Greek theatre mask.

Unfortunately the masks were made of organic plant stuffs, similar to papier-mâché thus none have survived history. But I believe they were painted with white for the flesh, black around the eyes and eyebrows and red for the lips. A good example of this is the modern ‘French’ mimes with face paint that is outlined around the jaw and chin with black, black around the eyebrows and eyes, white over the face and red on the lips and sometimes cheeks. Mimes also earn their name from Pantomimes which comes from the ancient theatre as “imitates all” meaning they spoke, danced, played music etc. The silent aspect of their performance was a later addition.

Harlequin is first attested to Orderic Vitalis in the 11th century, where he claims he was haunted by a troop of demons led by a black masked giant named familia harlequin, a description that reminds me a lot of satyrs, Pan and the retinue of Dionysos. By the time of the Renaissance the Harlequin evolved into a stock fool character for plays as either a servant of the devil or the devil himself. Noted for despite his large appearance he is nimble physically as his role often involved some form of foolery and acrobatics.

Clowns are the most ancient performers known with references of clown characters found in ancient Egypt royal courts, 4500 years ago. (12) A fascinating aspect of the clown is that they have a long history of being associated with priests and healers, in some cases the role was actually filled by a member of the priestly caste. Anthropologists relate clowns to the Heyoka, with many Native American tribes considering clown shamanic powers to be the most powerful. The shaman healing aspect is not unique to Native American’s, similar roles are found in shamanic traditions of Europe, Africa and Asia too.

Even now modern Clown doctors can be found mentioned in medical essay’s for their effectiveness recognised in western medicine, proven by performers like Patch Adams, Hunter Doherty:

Their activities include entertaining bored children and mothers in crowded outpatient clinic waiting rooms, distracting anxious families in inner-city emergency rooms, comforting parents of children in intensive care units, and distracting small AIDS or cancer patients during painful and frightening procedures. They spread joy and mayhem wherever children might be found in what is otherwise an environment not designed with children in mind.” (13)

Of course with associations with healing comes also the chthonic relationship too. Shamanic practices often cite clowns as either scaring off or being possessed by the dead. No doubt being linked with illness and healing would lead to this.

The modern appearance possibly originates from the Italian Commedia dell’Arte, as the Pierrot (foolish victim) or Pulcinella stock characters usually dressed in white, loose robes, sometimes with red frills around the neck. In a classical context Pierrot, akin to the mime, fits nicely into the description of the chorus in most Greek plays, typically they were white robed and wore plain masks. The chorus sometimes plays a shamanic role as an intermediary between actors and audience, thereby breaking through the Fourth wall.

As the circus developed in more modern times clowns adapted into what we know of today. An interesting result of pop culture and connections with figures like John Wayne Gacy (and attacking clowns in France this year) clowns have once again regained their associations with death and despite positive work in hospitals performances featuring clowns are being cancelled, some even feature warnings for people who suffer coulrophobia. (14)

Street Magicians appear to be an art form that has barely changed throughout history. (As already mentioned by Alciphron’s account.) The Conjurer by Hieronymus Bosch (1502), features a street magician performing a similar trick as the cups and balls, in the painting the magician wears black and red attire (akin to the Harlequin) and holds up a snail shell instead of a ball. The second central character is a man dressed in white and red (akin to the Pierrot?) who appears to be a gasping in shock at the trick. While difficult to see in most reproductions online, he actually has a frog coming out of his mouth, symbolising loss of reason and succumbing to animal instincts of disbelief, a foolish victim. Art commentators often mention how Bosch uses these two figures to deceive the viewer as their clothing draws the eye, a casual viewer can easily miss the thief stealing the victims coin purse to the far left.

The overall theme of the painting is attributed to Flemish proverbs:

“He who lets himself be fooled by conjuring tricks loses his money and becomes the laughing stock of children.”

“No one is so much a fool as a wilful fool.”

The criminal association is not just found with Bosch and these proverbs, other Middle-age commentators are critical of street performance and sort it being banned. Classical theatre was outlawed by Emperor Justinian in the sixth century and thereafter performance was viewed by Christian leaders as being a pagan act, equating it to other criminal activity such as thievery and prostitution. The English parliament of King Henry IV even partly blamed street performers for rebellion in Wales:

No westours and rimers, minstrels or vagabonds, be maintained in Wales… Who by their divination, lies and exhortation are partly cause for insurrection and rebellion now in Wales.” (15)

These fears of street performance continue into the modern age by the authorities, especially in Europe, where there is an increased of anti-social laws in public spaces – despite social studies reporting busking activity actually decreasing crime rates and establishing a sense of safety to the public. (15)

Modern street performers cannot be generalised easily. They are made up entirely by individuals that do things their own way, each with an unique act. They are not sponsored or funded by any other business than their own, yet a good number travel around the world each year living in perpetual summer. Some are professionally trained from world famous circus groups, others are self-taught or trained in a sort of apprenticeship. Their skills are acquired through practice, hard work and failure. Apart from learning their tricks they also learn to master the act of engaging with the public, a task that is quite difficult. I’m often amazed not just by their act but how they gather crowds. You can see their charisma at work when they start out as some funny looking person standing in the middle of the street yelling like a madman, to being the centre of attention of a hundred or more people in less than ten minutes. The most experienced performers make this look simple, however when you see the beginners you realise just how difficult it is to stop people for a moment to watch.

In regards to traditions, many street performers still follow the customs of the circus, even if they’re not conscious of it. Of note: those I’ve watched often wear red, black and white. I asked one performer why he chose to wear the colours and he informed me that apart from being attention grabbing, they are colours he is comfortable performing in.

While some may have forgotten their historical backgrounds street performers still maintain the Dionysian spirit, not just in their occupation and travelling lifestyle. Currently there are several organisations established by street performers with aims of fighting the constricting laws in cities around the world that prevent free speech and performance in public. In many cases they are succeeding against a system that affects everyone’s right to freely express themselves. Often these organisations are the only ones that are fighting these issues and bringing light to these invasive laws that are passed through government without media acknowledgement. To that extent they are like the technitai as ambassadors between the public and government.

We live in a world entrenched in so much information that is provided to us by corporate businesses, governments and politically bent media. Rarely do we get to see an individual’s perspective of the world, especially an individual that has resisted the set expectations of what culture presumes of them. Performers prove that we can be free, that anyone can make their own life on the street not only with dignity but also admiration. From my own perspective the service I provide is paid for not only with generous donations from the people, but also the incredible support and encouragement that is constantly shown to me while I work. In times where I’m feeling a bit dishearten by what is happening around me, it’s always beautiful to realise that the horrors in the world are mere minorities to the kindness of the majority.

To finally finish this piece I would like to quote Owen Lean , a street performer, from the Busker Hall of Fame:

We live in a society where we have repressed a lot of our animal instincts in striving for order – yet inside of us that animal is screaming and fighting to get out, and every now and again we need that release.

This is what street performance does. We, the busker, stand right in the centre of the urban environment, right in the middle of this 9-5 world of straight lines and literally pull our audience out of it for twenty minutes and we do our job right, turn them into children again, allowing you to experience a different world, a world where the rules are broken, and where you’re not only allowed but actively encouraged to play.” (17)

Sources:

1 Richard Seaford, Dionysos; 90

2 Section 3: Ancient Greek Comedy, Chapter 8: Early Greek Comedy and Satyr Plays

http://www.usu.edu/markdamen/ClasDram/chapters/081earlygkcom.htm

3 Trans. P. Dickinson, Oxford U.P, Plays; 171

4 Bonnie MacLachlan , Kore as Nymph, not Daughter:Persephone in a Locrian Cave

http://www.stoa.org/diotima/essays/fc04/MacLachlan.html

5 / 6 Eric Csapo & William Slater, The Context of Ancient Drama; 233, 244

The 279 BC Delphi Degree:

It was decided by the Amphictyons and the hieromnemones and the agoratroi: In order for all time the technitai in Athens may have freedom from seizure (asylia) and from taxation, and that no one may be apprehended from anywhere in war or in peace or their goods seized, but that they may have freedom from taxation and immunity accorded to them surely by all of Greece, the technitai are to be free of taxes for military service on land or sea and all special levies, so that honours and sacrifices for which the technitai are appointed may be performed for the gods at appropriate times, seeing that they are apolitical (apolypragmoneton) and consecrated to the services of the gods: let it be permitted to no one to make off with the technitai either in war or in peace or to take reprisals against them, provided that they have contracted no debt with the city as debtors, or are under no obligation for a private contract. If anyone acts contrary to this, let him be liable before the Amphictyons, both he himself and the city in which the offence was committed against the technitai. The freedom from taxation and security that has been granted by the Amphictyons is to belong for all time to the technitai at Athens, who are apolitical. The secretaries are to inscribe this decree on a stone slab and set it up in Delphi, and to send to the Athenians a sealed copy of this decree, so that the technitai may know that the Amphictyons have the greatest respect for their piety towards the gods and adhering to the requests of the technitai and shall try also for the future to safeguard this for all time and in addition to increase any other privilege they have on behalf of the Artists of Dionysus. Ambassadors: Artydamas, poet of tragedies, Neoptolemos, tragic actor.

7 Livy, History of Rome, Book XXXIX

http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/ancient/livy39.asp

8 The Letters of Alciphron via Christopher Milbourne , Magic: A Picture History

9 Plato, Republic 363c; 364a–365b

10 Edited by Bettina Bergmann and Christine Kondoleon, National Gallery of Art, Washington, The Art of Ancient Spectacle; 259

11 http://thehouseofvines.com/2014/01/27/confirmation-of-a-taboo/

http://thehouseofvines.com/2014/01/27/puppies/

12 Michael Bala, Jung Journal: Culture & Psyche Volume 4, Issue 1, 2010, The Clown An Archetypal Self-Journey

13 Linda Miller Van Blerkom, Clown Doctors: Shaman Healers of Western Medicine

14 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clown#Fear_of_clowns

15 (Jusserand 1950, 113) via Kalli R. Fullerton, Street Performers and the sense of place.

16 Susie J. Tanenbaum, Underground Harmonies: Music and Politics in the Subway of New York

17 http://buskerhalloffame.com/the-story/contributors/owen-lean/why-were-necessary/

More info:

http://buskerhalloffame.com/

http://blog.buskr.com/

Image info:

1 Theatrical masks of Tragedy and Comedy.

Roman artwork

2nd century CE.

Public Domain

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:TragicComicMasksHadriansVillamosaic.jpg

2 Ooooh I’m a Mime

Tyler Mestas

11 May 2013

CC copyright

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ooooh_I%27m_a_Mime.jpg

3 The Conjurer

Hieronymus Bosch

1496 – 1529

Public Domain Image

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hieronymus_Bosch_051.jpg

4 Shove tuesday (Pierot and Harlequin)

Paul Cézanne

1888

Public Domain Image

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Paul_C%C3%A9zanne_060.jpg

A special thanks to H. Jeremiah Lewis (Sannion) for introducing me to this subject and his continual free publication and research found on his blog: thehouseofvines.com